A Brief History of Shibari - Part 1 - Content-Image-Reflection

If you've spent enough time perusing the catalogue of the now-defunct R18 (or the still-up-and-running DMM), you've probably seen this image: A beautiful woman, hands tied behind her back and body wrapped in a cat's cradle of rope. The rope encircles her breasts and perhaps suspends a leg or her whole body. And sometimes in the frame someone older (and in many cases uglier) leers at the woman like a spider at captured prey.

This is shibari, Japanese rope bondage. And if you've seen this image before, you might wonder at some point where this genre of AV came from. It is, after all, rather different from the leather whips and metal chains one finds in Western bondage, which would suggest a different history and impulse behind it. So in this series of articles, I'd like to discuss the history of shibari: how it started, how it was popularized/codified, and how it took its modern day form. For Part 1, this part, let's look at how shibari started.

Rope has always been a part of Japan. If you want an indication of its ubiquity, just look at the Shinto shimenawa you can find in shrines or around trees, or how samurai armor and courtly kimono don't use buttons or zippers as fasteners, but rather rope. Indeed, the word Jomon, from which Japan's first historical period (14000-300 BCE) is named, comes from rope-imprint patterns found in pottery dating from that period.

Why this abundance of rope? Well, largely it's a matter of geography and resources. Japan is an island nation stuffed with mountains, so there's not a lot of flatland. And what flatland exists has historically been set aside for rice fields, since that's everyone's main source of sustenance. So there's no space for large, leather-making livestock to live, thus rendering tanned hides a rare commodity back in ye olden days. Rice straw and hemp though are common and plentiful, and humans are always going to find some way to use whatever resources they have.

Given all this, it should come as no surprise that rope became ubiquitous in Japan, and eventually found its way into the hands of lawmen. After all, what better way to apprehend a criminal than to lasso them with a lariat? And with the Edo Period (1600-1868) ushering in a new age of peace and prosperity for the country, even commoners found themselves with free time and spare cash to spend on things like drink, paintings, and the theater.

These two things may seem like unrelated developments, but they actually converge in an important way with shibari's history. See, visual art like Kabuki plays rely on visual shorthand. Through simple, effective imagery that everyone recognizes, you can show details of a story without needing to tell the audience things through dialogue. For instance, if you see cobwebs in a film, that implies that many, many years have passed. Even though a spider can spin a full cobweb in an hour, cobwebs have become such a visual shorthand for the passage of time that it would feel weird to most viewers if they saw a cobweb show up in a different context. With regards to rope, most people in Edo Period Japan knew that police officers used rope to apprehend and torture people. They probably even witnessed a few arrests on the street themselves, saw actual crooks getting tied up and carted away. So when Kabuki plays needed a visual shorthand to signify that a character was in a bad spot, rope was an obvious choice. If you see a character tied up, you know to be frightened for them, as sure a signal as any eerie music.

Here's where things get fun. I said that the Edo Period gave people a lot of new income and free time to spend on entertainment. But even so, Edo Period kabuki plays weren't going to be as widespread as something like modern-day Netflix, simply because there were only so many seats at so many showings of so many theaters in so many cities. If you lived in the countryside, or even just outside of Edo (now Tokyo), you simply weren't going to see any of these plays. But you might see the ads for them.

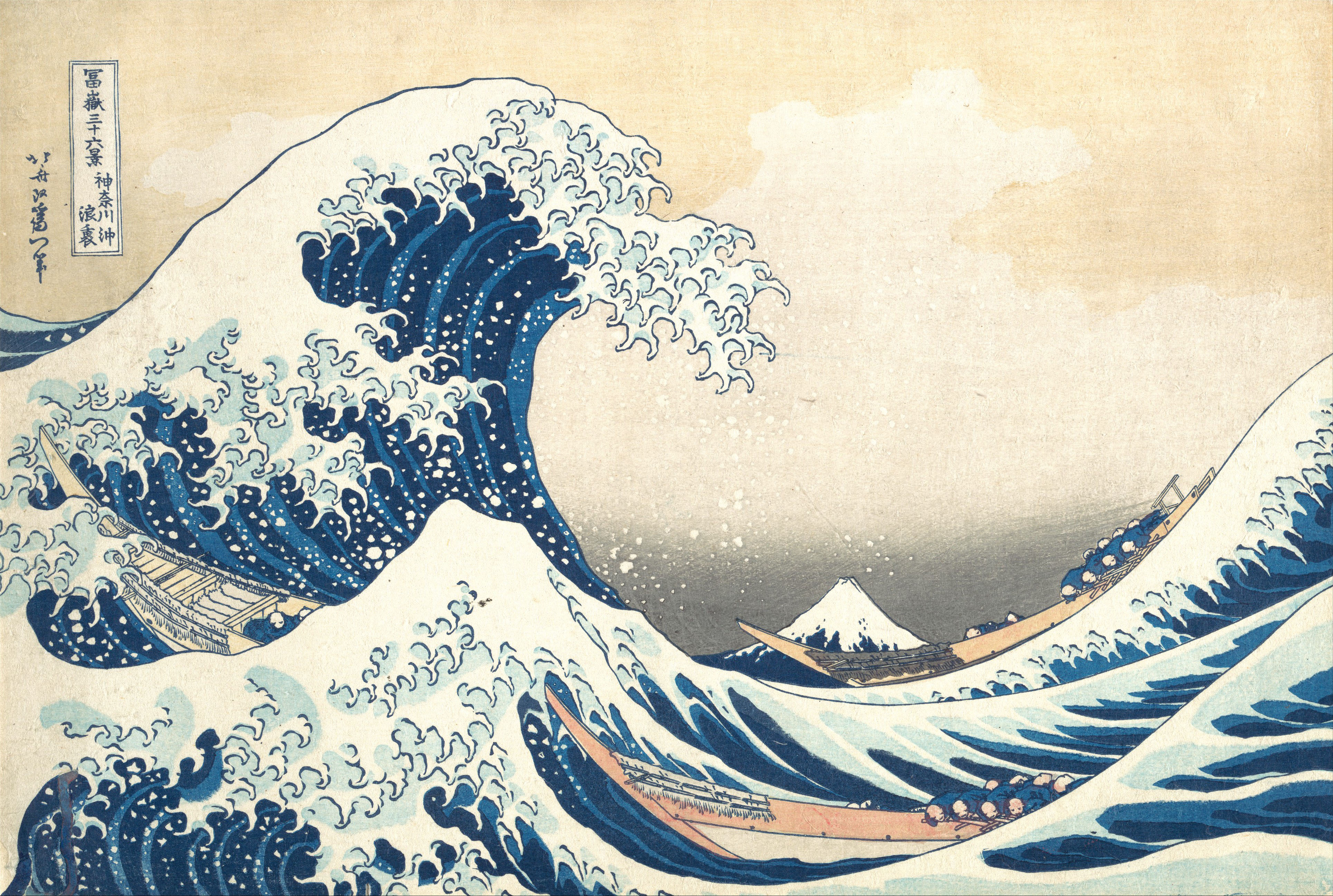

An image you all are no doubt familiar with

Ukiyo-e, the pictures of the floating world, are something most people have seen, even if they know nothing about Japan, and there's a reason for that. These paintings were made on cheap woodblocks, designed to be made quickly and distributed easily. And to many folks outside of Edo, they were probably the only images of that city and its lifestyle that they saw. With regards to rope, many ukiyo-e were drawn to reflect particularly lurid or gruesome scenes from kabuki plays, serving the same function as movie posters, to be passed around and generate interest in the plays. Let's face it, sex and violence sell, and through these ads, rope became associated with sex and violence, to let people know that there would be blood (or tits) in this particular play.

The thing is, this kind of advertising can be even more influential than the thing it's supposed to advertise. Remember, John Carpenter grew up in the middle of nowhere with no tv, but he was still able to draw enough inspiration from a theater trailer for The Quatermass Xperiment to develop what would eventually become The Thing. And even if none of us can watch the cabaret performances of Aristide Bruant anymore, his image lives on and continues to inspire, thanks to the famous poster of him by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. (Indeed, if you're a fan of British sci-fi, you may already know a character whose look was directly influenced by Bruant.) Singular images are enough to spark the imagination, which fills in the blanks of the image's context with the viewer's own proclivities and prejudices.

From this progression of the real-world justice system to the fictional portrayals of that system to advertisements of those portrayals, we see how shibari finally began to take hold of the imagination of Japanese people. But this progression also demonstrates the larger pattern of how kinks and fetishes are formed in general.

From this progression of the real-world justice system to the fictional portrayals of that system to advertisements of those portrayals, we see how shibari finally began to take hold of the imagination of Japanese people. But this progression also demonstrates the larger pattern of how kinks and fetishes are formed in general.

Kink springs from a three-step progression of content, image, and reflection. There is some real-world phenomenon that is signified with a particular visual, and then when that visual is applied to a different context, it can take on a new meaning. Take, for instance, spanking. Many of us were probably spanked as children, and it wasn't a fun experience. However, as adults, if we or our partner play-act this situation, it can take on a new meaning. What once made us cry can now make us laugh or cum, now that it's done playfully with negotiation and consent.

The cops who catch criminals are the content. They apprehend and torture people, but the rope they use is simply the tool they've been given to carry out this task fundamental to their job. This content is now given an image for a general audience through the kabuki plays that feature it. How do we show the audience that this character is being apprehended or tortured, without actually harming the actor playing said character? Tie them up in a way that looks frightening, but is actually quite comfortable for the actor (in contrast to the real-life rope ties, which were deliberately designed to hurt). Now, just as we associate the sound of coconuts with horse hooves, or whizzing noises with flying bullets, Japanese audiences associate shibari rope with gruesome scenes. And then, the ukiyo-e woodblocks reflect this notable, lurid image from kabuki, and are distributed far more widely than a play at a single playhouse could ever be. Even if you never see a kabuki play, chances are you will see a woodblock about it, and that image of a beautiful woman bound up, divorced from its original context, can now take on a meaning that you give to it. Sure, maybe it's meant to be scary, but isn't it just a little bit sexy, too? Doesn't it scare you stiff? (I'm sorry, I couldn't resist.)

So that's how sexy shibari began to take root in Japan. But it still hadn't yet blossomed into its modern day form. It would need a horticulturist in order to grow to full bloom, and that horticulturist would come in the guise of the painter Seiu Ito...

Special thanks to my BDSM Teacher, Midori, who was a big help in writing this article. You can find her website here, her Patreon here, and her Twitter here. Also special thanks to my friends in academia, who also helped out a lot.

Further reading:

Midori - The Seductive Art of Japanese Rope Bondage (2001)

Enrico Paolini - Ningyo Sashichi and Hanshichi: Differing Views on Ancient Edo (2020)

Comments

Ooh, yes. Ayumi Shinoda has just the right expressive face for shibari scenes.

By Baskerville @ July 30th, 2020

By RamenBoss @ October 23rd, 2021

By WoodOfTheRisingSun @ October 22nd, 2020